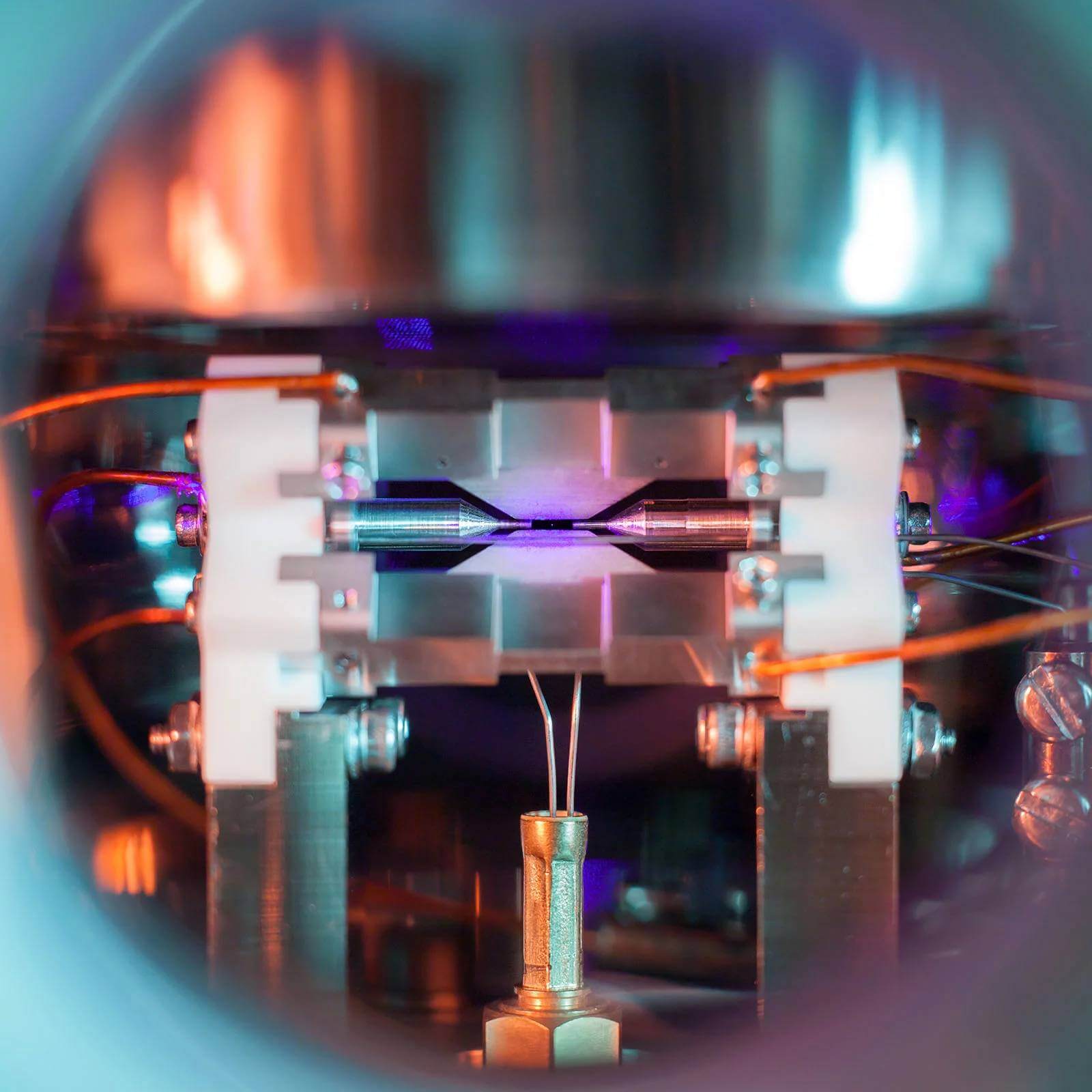

We are all made of atoms and everything we can see around us is made of atoms. But, have you ever seen a single atom? A remarkable photo of a single atom trapped by electric fields was shot by David Nadlinger of the University of Oxford and you’re about to see it below.

The photo is titled “Single Atom in an Ion Trap”. The author said about it for EPSRC:

“The idea of being able to see a single atom with the naked eye had struck me as a wonderfully direct and visceral bridge between the miniscule quantum world and our macroscopic reality. A back-of-the-envelope calculation showed the numbers to be on my side, and when I set off to the lab with the camera and tripods one quiet Sunday afternoon, I was rewarded with this particular picture of a small, pale blue dot.”

The photo was captured on August 7th, 2017, using a Canon 5D Mark II DSLR, a Canon EF 50mm f/1.8 lens, extension tubes, and two flash units with color gels. It is a winning photography in a well-known science photography competition held by The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

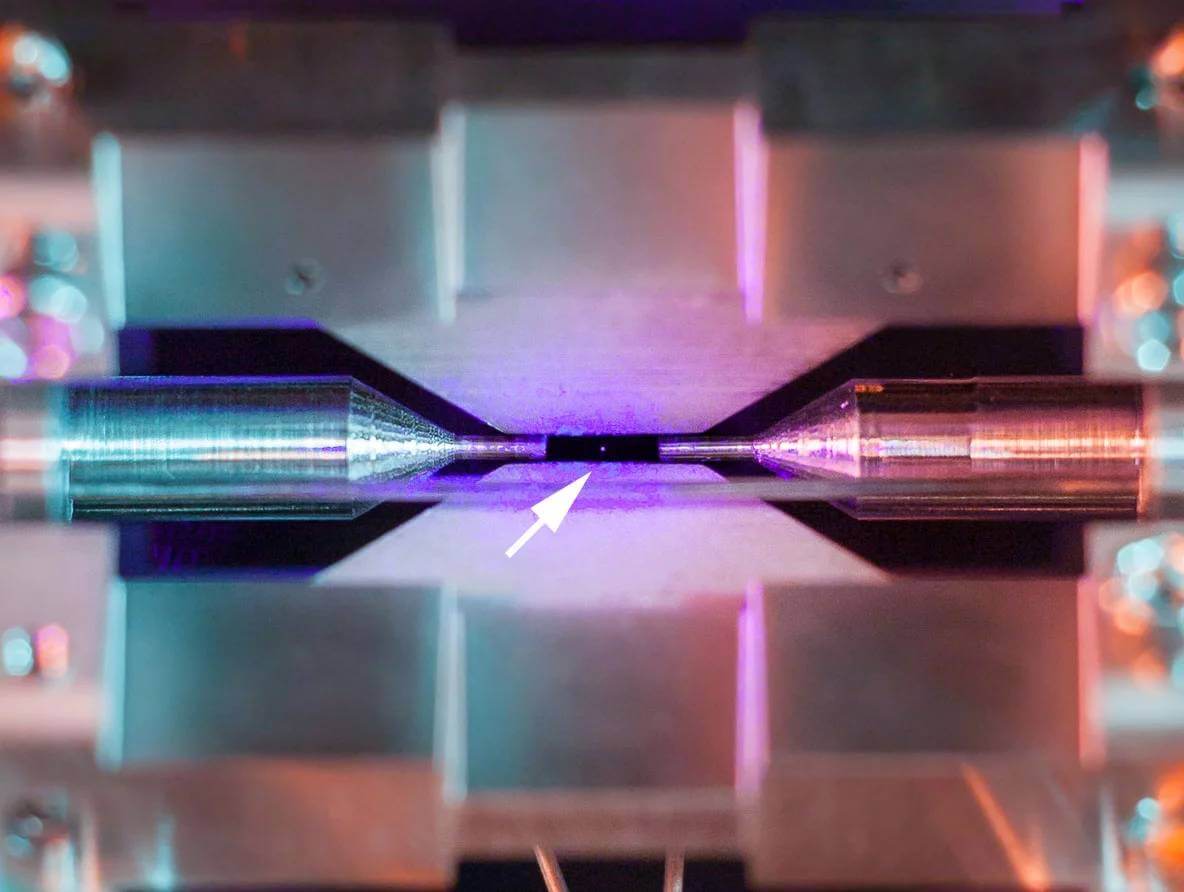

“Single Atom in an Ion Trap” by David Nadlinger of the University of Oxford.

Single atom being suspended at the center of the frame.

Image credits: Photograph and crop by David Nadlinger, courtesy EPSRC

The caption:

In the center of the picture, a small bright dot is visible – a single positively-charged strontium atom. It is held nearly motionless by electric fields emanating from the metal electrodes surrounding it. […] When illuminated by a laser of the right blue-violet color, the atom absorbs and re-emits light particles sufficiently quickly for an ordinary camera to capture it in a long exposure photograph.

This picture was taken through a window of the ultra-high vacuum chamber that houses the trap. Laser-cooled atomic ions provide a pristine platform for exploring and harnessing the unique properties of quantum physics. They are used to construct extremely accurate clocks or, as in this research, as building blocks for future quantum computers, which could tackle problems that stymie even today’s largest supercomputers.

Via: petapixel